The Chatham Fair

My intention had been to write a quick reminiscence of the Columbia County Fair — AKA the Chatham Fair — but the end result is more like a book. And that is as it should be. The Chatham Fair was an integral part in the tapestry of life as I grew up, and anyone who lived in that area at that time will undoubtedly harbor similar memories. If so, I encourage you to share them.

Ah, the Chatham Fair, that festive bookend of the summer season, the annual orgy of sights, sounds, smells and sensations, softening the blow of the coming school year.

The fair would roll into town on the Thursday before Labor Day Weekend, erected in mere hours, and open that evening. It ran for the entire weekend, ending on Labor Day Monday. On Tuesday, it would be gone, and on Wednesday we’d start school.

It was, and remains, such a perennial event, that I never thought to wonder why, or ruminate on how fortunate we were to have this eagerly-awaited event occur at such an opportune time. It had, after all, been going on for over a hundred years by the time I became aware of it; it was simply there, and I assumed it always would be, as indeed—to this day—it is.

As a boy, a teenager, and a young man with a family, the routine of the Fair—aside from those few exceptions when, during my teen years, I snuck in by jumping over the back fence—remained unchanged.

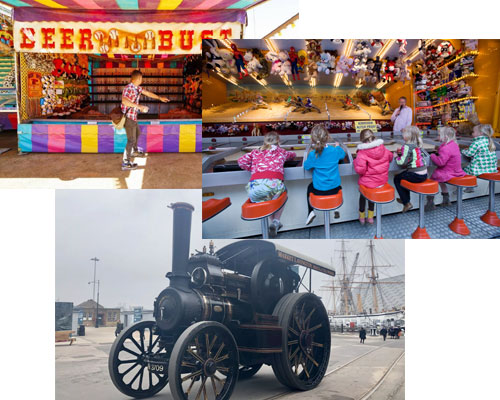

First, we would visit the 4H Exhibits in the big pavilion buildings, looking over artwork, embroidery, quilts, green beans, beets, pumpkins, squash, jams, pickles, and anything enterprising youngsters might put their minds to. After that, it was the animal sheds: long buildings with rows upon rows of cages containing all manner of chickens and rabbits—some quite exotic—followed by the exhibit of old traction engines, steam-powered vehicles and, ancient tractors. After that, it was the pole barns, where sheep, goats, and cattle were kept, and where their owners slept. That was what I found most interesting, not the livestock, but that fact that the kids exhibiting them actually slept in the straw alongside them. That, to me, defined dedication.

I’d like to point out that, even as a kid eager to get to the rides, I found none of this boring. It was a time-honored ritual, and in later years, when I came on my own, I still followed this trail to the pot of gold at the end: the Midway.

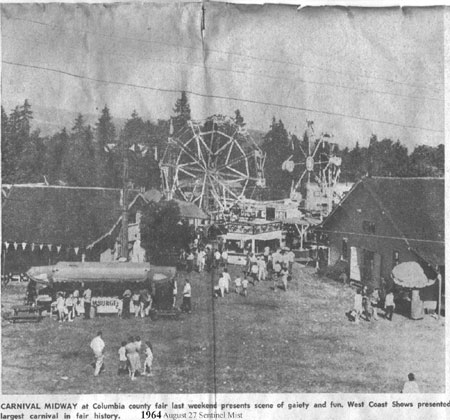

This was the heart of the Fair, a huge swath of rides, games and shows running the length of the field, ending at the grandstand, where the show ground, performance stage, and racetrack were located.

The center of the Midway was where the rides were, from the rather tame teacups to the more hair-raising twisting, spinning, diving rides. (These are even more hair-raising in retrospect, when you consider how quickly they were slapped together by people who most likely didn’t even have a high school diploma.)

The Midway was filled with the sound of engines, loud music, and the delighted screams of people on the rides, coupled with the smell of diesel fumes, burnt sugar, and dust. I’m sure it must have rained on some of those weekends, but in my memory, it was always sunny and hot, and the summer-dried ground sent up puffs of gritty dust as we walked among the rides.

To one side were the games, with barkers encouraging you to step right up and lose your money. As a small boy, these guys were terrifying (“Three tries for a dime, sonny! Try your luck!”), as a teenager—occasionally with a date or at least a friend—they were embarrassing (“Win the little lady a prize! You know she wants you to!”), and as an adult, a simple annoyance. I did like playing the games, but winning anything was stupid, because it was always something useless, like a paper bird on a string, or a live goldfish in a plastic bag that you then had to carry with you for the rest of the day knowing it was going to die the moment you got it home.

On the other side of the fairgrounds, near the trailers where the carnies slept, were the sideshows.

It’s cringeworthy to say in this day and age, but back when I was young, even into my teens, this segment of the Fair was called The Freak Show. This was where you could see the Snake Woman, or the Wolf Boy, or the Tattooed Lady. And, of course, the Hoochie Coochie Girls (“She walks, she talks, she crawls on her belly like a reptile!”). The latter were, I believe, strippers, but I can’t verify that. I was too young for admission and not bothered enough to sneak under the tent flaps in the back. In fact, I tended to avoid this area, knowing it be a bit of a rip-off, though my curiosity was occasionally piqued.

I paid to see the Snake Woman, and found myself alone in a tent with a young lady ensconced inside a pedestal with her head poking through a cushion, as if there was nothing to her but her head. It was so obvious that I just had a quick look and, embarrassed for her, quickly left. I also ended up in another exhibit, where a man born without arms, took a pouch of tobacco and rolling papers out of his coat pocket, rolled a cigarette, and lit it with a match, all using his feet. That impressed me. What did not was “The Fiercest Gorilla in Captivity,” or some such nonsense. Why I paid to go in I’ll never know, but I sat with a dozen or so other punters while a man in a gorilla suit tried to scare us, and then broke his chains and rushed the audience, causing his handler to shoot him with a blank gun. If they had played it for laughs, instead of trying to pretend it was really real, it might have been worth whatever the admission price was.

My earliest memory of the Fair was getting into the octopus ride with my mother. If you are only familiar with the cushioned, seat-belted seats of today, you cannot imagine how basic the rides of my youth were. No restraints, no padding, and as a consequence, when the car rose and bounced, I bumped my face on the sharp metal of the door frame. Blood appeared. Not a lot, but you don’t need much to make a 4-year-old panic, and for the next ten minutes, until the ride stopped, I did all I could—kicking and screaming—to wriggle out of my mother’s arms and jump out of the moving—and well above the ground—car. How my mom kept hold of me I will never know, but I am grateful to her to this day.

Thanks for not letting me kill myself, Mom. You’re a real hero.

As an older child, and teenager, I spent most of my time in the Midway going on the rides and eating cotton candy which, along with fried dough and candied apples, were standard fairground staples. The fried dough was good, but I liked spun sugar best. A candied apple—in my view—was just a waste of a good apple; you couldn’t break through the hard, not-found-anywhere-in-nature-red colored shell, and the process made the apple mushy. After my first try, I thereafter gave them a miss.

As time went on, the rides became more scary, and I rose to the challenge. I loved the spins, the dives, the dizzying heights, the twists and loops, and, oddly, so did my dad. He even went on one of the more adventurous rides with me when I was a young teenager, and admitted that, when it came to the Fair, he was like a kid. I had never seen him quite so happy. That’s the effect the Fair has on you.

As I became older, and acquired a car, it was a great place to bring a prospective girlfriend, which led to one particularly memorable afternoon.

I was probably about twenty years old, and with a girl I had recently met and had designs on. We were getting along well, and then I took her on The Swinging Basket ride, or whatever it was called. The ride consisted of a metal cage on long pendulum that, if you used your body weight, you could swing. The idea was to swing it so far that it did a complete circle.

We got into the cage together, facing one another, holding the handles on either side, and then started to rock. Keeping in time with each other, we swayed, slowly, gaining speed and urgency as we rose higher and higher, pushing, pumping, gasping, sweating. We moved back and forth, pushing harder and harder, at last nearing the pinnacle. One final thrust was all we needed to push us over the top. I leaned hard in one direction, then swung my body as fast as I could the other way, hoping to gain the necessary momentum.

And the top of my head hit her square in the face.

Long story short: there was blood, we failed to make it to over the top, and I did not get a goodnight kiss.

(The strange thing about this story, aside from it being absolutely true, is that we ended up becoming good friends.)

I’ll share a final memory of the Fair, because it was truly interesting, and there is a moral:

When I was sixteen, some friends and I hitch-hiked to the Fair on its final day. We spent the afternoon and evening doing what you usually do at the Fair, and somehow ended up helping the carnies take it down.

That was the hardest work I had ever done (but, to be honest, the bar was set pretty low) and it showed me another side of the fairground: the gritty, nuts-and-bolts, everyday life of those on the road. And, although it was not easy, it was companionable and engendered a sense of camaraderie. I worked long into the night carrying heavy bits of metal, that had not long before been the Tilt-a-Whorl or the Scrambler, to the waiting trucks and the knowledgeable hands of the carnies. They knew exactly where to stow each piece, and it amazed me how an entire county fair—rides, games, tents, fences, kiosks, hoses—could fit into a surprisingly few number of trailer trucks.

We worked until I thought I would drop from exhaustion, and then worked some more. At around 3:00 AM, we finished, and were rewarded with an amount of money I was very happy with. Then we left the empty fair ground and went to Main Street Chatham. It was, naturally deserted. We were hungry, tired, dirty and just wanted to go home, but there was no way to get there.

Then I remembered something my dad had said to me some months before. “If you’re ever in a tight spot,” he told me, “and you need help, call me. I might not be happy about it, but I will come and get you.”

I told my friends this and we agreed it was the only thing we could do. So, we hunted up a pay phone (explain it to the youngsters), called, and…ended up sleeping on the sidewalk.

These were everywhere back in the day, in booths (called “Phone Booths”)

on practically every street and in every bar or restaurant.

You would turn the dial with your finger to dial a number,

insert coins into the slots, and talk to someone.

I am not making this up! Google it!

I wasn’t surprised by this, or particularly bothered. We hitch-hiked home the next morning, and life went on. But I always had in the back of my mind the knowledge that my dad had made a promise, and that he broke it. And this made me determined that, when I had children, I wouldn’t do this.

So, when my boys grew into teenagers, I made certain to never promise them anything quite that stupid.