Rainy Day Play or Life Before Cling Film

Cling Film or plastic wrap (what we called Saran Wrap in the US), was invented in 1949 but wasn’t widely used until I was older. What we did have when I was young was wax paper, which was just what it sounds like: a thin film of paper coated in wax.

Mom used it for lining dishes that were not going in the oven, and I recall her using it to press hamburgers. It was great for holding sticky things like fudge, and was even used to wrap the sandwiches we took to school. But what we used it for was tracing paper.

It was the ideal medium—translucent and with a film of wax on both sides. This allowed us to put it over a picture, trace it, then transfer the tracing to a piece of paper or cardboard so we could colour it in. As I recall, what I mostly copied—because I was a nine-year-old boy—was dinosaurs.

This was possible because, back then, almost every home had a set of encyclopaedias.

We were not particularly well-off. In fact, you might say we were poor (or at least impecunious) but we had several sets: Grolier, The Book of Knowledge, Lands and People, a science encyclopaedia, and a set of Childcraft books. The dinosaurs were in the science books, and they provided many hours of diversion.

On rainy days, we would pour over the books, revisiting favourite parts (like the dinosaurs) and exploring new subjects. This was our Internet. Those books were the source of all knowledge, they were what we turned to when we needed to know anything and, during our teen years, they were invaluable for researching essays (or, more likely, copying text straight out of them and passing it off as our own work).

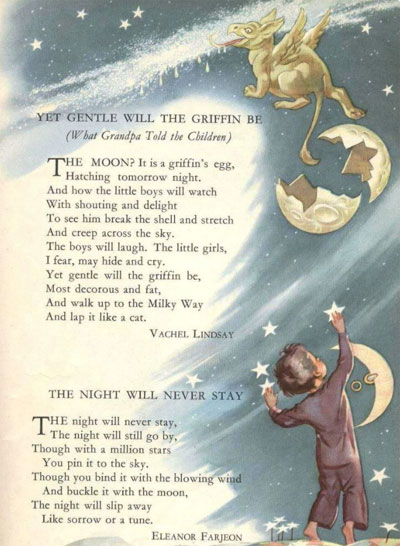

Despite the lure of the dinosaurs, the books I mostly turned to were the Childcraft Encyclopaedias. It was there I learned all the poems of childhood, the familiar (Jack be nimble, Jack be quick), and the obscure (Yet Gentle will the Griffin Be, or What Grandpa told the Children: “The moon? It is a griffin’s egg, hatching tomorrow night…”) I can still recite most of them from memory and I advise, if you ever encounter me at a gathering, to not test me on this unless you are prepared to be bored to tears.

So loved were these books that, when we left home, the five of us divided them up and took them with us. I ended up with volumes one and two, which contained the poems. I have recently sent these to my grandchildren because I don’t need them any longer and I wanted to afford them the opportunity to carry these (most likely forgotten) poems into the next generation. (Little Boy Blue, come blow your horn, the sheep’s in the meadow, the cow’s in the corn…)

When I wasn’t memorizing poems or tracing a Triceratops, I would sometimes play Battleship with my siblings. No fancy game-board for us; we just got a piece of paper and grew a graph on it. (And we liked it that way.)

Another item I had that filled many an empty hour was my bottle cap collection.

As I recall, at a very young age, I was at Charlie Barton’s garage, buying a soda from the vending machine when Charlie was emptying the hopper that held the bottle caps. I asked if I could have them and, very kindly, he gave them to me. I added to this collection over the years and eventually had a big box full of them.

(Back then, there were no screw caps, and bottles came with a metal and cork cap that you had to pry off. I wrote about this in Changes.)

During long afternoons with nothing to do, I would build castles out of them, using the caps like interlocking bricks, constructing double-thick walls with turrets on each end. It took hours. And then I’d set up my brother’s Hot Wheels set and launch the little cars into it to knock it down.

I did this well into my teenage years and was very protective of my collection. So much so, that when I eventually donated it to a friend to use in a craft project for a Bible school (this was during my Jesus Freak years—more on that at another time) and she later confided in me that she never got around to using them, I went to the church and talked the pastor into allowing me to rummage through the attic of the sanctuary—where all the cast-off stuff ended up—until I located it.

At some point—I don’t recall when—I left it with my son for safe-keeping but, as the years went by, the metal rusted and the cork rotted, and the entire collection had to be thrown out.

And so, my bottle caps, the encyclopaedias, and the reams of paper—all the things that kept us entertained on inclement days—are gone now.

But I can still recite the poems. If you don’t believe me, just ask.

20 March 2022