My World, Expanded

By around the age of 10 or 11, I was able to explore further afield. On my own, that is. I was still very close to my sister at that time and, through her and her boyfriends, I travelled to many locations not attainable by walking or cycling. But I’m not talking about that now. These are the locations I visited on my own.

This installment details the local area I grew up in, which had a rich history:

1. My house.

2. We called this “The Corner.” It was where we waited for the bus. From the age of five—along with my sister and the neighbor kids—I walked the quarter mile to wait by the side of 9H for the school bus. No one thought this was unusual. Naturally, when we were older and could very well walk by ourselves, they changed the bus routes and picked us up in front of our homes.

3. This was what was left of the Lindenwald Estate, where President Martin Van Buren lived after he retired. The imposing Federalist mansion was—miraculously—still in pretty much the same shape as it was when Van Buren owned it. There was only one gatehouse left, to which Mr. Campbell—the old guy who owned Lindenwald when I lived there—added a covered area where he had an array of interesting, old junk laid out. A sign by the side of the road read, “Antiques,” but he didn’t do a lot of business as far as I could see. I used to go up there on occasion to rummage through the many fascinating items. During my early teens, I bought two French sword-bayonets with inscriptions on the blades, for $10 each. They were cherished (and, perhaps, valuable) items, but The Cult made me sell them and give the money to them.

A history of this property is contained in a letter, written in 1934, by Mrs. W.B. Van Alstyne of the Columbia County Historical Society:

In 1667 Jan Martense Van Alstyne and his wife, Derckje, purchased from the Indians, and the ‘Thomas Powell Patent’ various pieces of land, aggregating about 3,000 acres, most paid for in beaver skins and grain. Jan’s granddaughter, Derckje, in 1729 married Martin van Buren and they were the grandparents of President van Buren.

In 1682 Jan’s son, Lambert, was living on 698 acres across the creek from Jan’s house, and had built a house. In an old deed there is reference to an ‘old stone house.’ This part of the land included the present ‘Lindenwald’ farm. This farm descended to Thomas and then to Lambert, son and grandson of Lambert van Alstyne.

Peter van Ness, the famous Columbia County Jurist, built the main part of the present mansion of brick in 1797, again acquiring lands south of the place in 1804 from William and Lambert van Alstyne and Lucas Hoes and Catherine, his wife. Peter and his wife are buried on the place west of the house on a knoll overlooking the creek and ‘Vly’.

William P. van Ness, son of Peter, inherited the farm in 1804. Later, the place belonged to a younger son, John P. van Ness, who evidently between 1835 and 1841 sold it on some sort of terms to Martin van Buren. There is no record of this sale in Hudson, but there is a record, (book MM, p 46) — ‘in a release of the same farm by John P. van Ness, Oct. 25, 1845’ — containing 200 acres. ‘In 1835, Oct. 28, Peter I. Hoes, Maria his wife and Lawrence van Buren parties of the 1st part to Martin van Buren 43 acres, for $2100.’ Thus van Buren regained property in his family on his mother’s (Hoes) and grandmother’s (van Alstyne) side.

Van Buren gave the name ‘Lindenwald’ to the place, coming there to live when he retired from the Presidency in 1841. He added the tower and library on the southwest side, and servants’ quarters across the back of the house. The paper on the walls on the hall, a spacious room in itself, is the original imported paper, depicting a hunting scene. Van Buren died in 1862.

Van Buren’s sons, Abraham and Smith T. conveyed the property to their cousin John van Buren, by deed dated May 6, 1863 (book 19 p 192-3) for $20,000 with about 230 acres.

April 11, 1864, John van Buren conveyed the property to Leonard W. Jerome (book 21 p 42) and Jerome to George Wilder, January 23, 1867 (book 28, p 221) also ‘17.6 rods to straighten out a line,’ Feb 7, 1872 (book 45, p 97) reserving the right to low-back water of Kinderhook creek as conveyed to Abram A van Alen. [The local legend I heard was that John—a flamboyant gentleman known locally as Prince John—lost the estate in a poker game.]

November 7, 1873 John van Buren and James van Alstyne purchased Wilder ‘Lindenwald’ for $35,000. (book 49 p 157—this is an excellent deed for information on property’s history.)

April 20, 1874 (book 51 p 17) John van Buren and wife and James van Alstyne sold the place to Adam E. Wagoner for $30,000.

November 15, 1917 (book 162 p 514) Adam E Wagoner and wife sold ‘Lindenwald’ to Bascom H. Birney; in all 220 acres consideration $1.00 (said to have been $15,000) Mrs. DeProsse is the youngest daughter of Dr. Birney.

This family has added some utility bathrooms, water system, hot air heat and slate roof. Otherwise, the property in not materially changed. Some furniture once owned by Martin van Buren remains in the house.

The land runs down to the creek, with fine views of the Catskills. On the fields south of the house used to be a small lake, and those fields are noted as an ancient Indian Camp site. Many arrow heads and implements have been found there. The ‘old stone house’ referred to was apparently near the road leading to the creek and perhaps near the farm barn and where the tenant house stands. There are two quaint gate houses, an interesting cottage and barns, and in back of the house facing a plateau, van Buren’s old coach barn.

In her disjointed ending, Mrs. van Alstyne mentions a Mrs. DeProsse as if knowledge of her is presupposed, which, in 1934, it was. Clementine DeProsse came into possession of the land on April 4, 1932—she received it from her mother, Marion Birney, (book 214 p 151) who had received it from Dr. Bascom Birney (book 201 p 162).

The Lindenwald mansion was, for a time, an Old Age home (this was likely during the time that Mrs. DeProsse owned it) and my mom used to work there as a teenager, doing laundry.

After I moved away, the US National Park Service finally took the estate over. It is now spruced up and is a pleasant place to visit, with woodland walks and lots of historical stuff to bore children with. A trail links this site with the Van Alen House (Item 5).

Martin Van Buren National Park

4. This was my Aunt Dorothy’s house, where she lived with her husband, Hank Cantine, and her son, Johnny, who was three years younger than I was. Before I started going to school, Mom and I used to walk the half mile up Rt 25 and the Old Post Road to visit her and Johnny. I remember it as a ramshackle house, with tarpaper on the outer walls and brambles encroaching on the tiny yard.

5. The Van Alen House. This is not to scale, as it is a bit further along 9H. This house—now a historical site— was built by Luykas Van Alen around 1737 and designated a National Historic Landmark in 1967. Incredibly, the house remained in the hands of the Van Alen family until 1961, by which time—as I recall—it had become so overgrown with weeds and brambles that the house was barely visible from the road. It was donated by the family to the Columbia County Historical Society, which undertook a complete restoration. It is now a historic house museum, showing 18th century Dutch Colonial life. The Ichabod Crane Schoolhouse (Item 6) was moved to the site in 1974.

The house came to our attention sometime around 1967 and we organized an expedition to go visit it. Melinda and I, and some of the neighbor kids, rode our bikes down 9H to the house, which was only about a mile and a half away. We had to leave our bikes near the road because the weeds were nearly impenetrable. As I recall, we had a hell of a time making a path to the house. By that time, it was little more than a two story, brick shell, with holes in the roof and old linoleum on the floors. It seemed the house was occupied up into the 1930s before it was abandoned. I mostly remember the cellar, which was dark and dank and had a few chains hanging from the beams. We declared that these were the chains they used to keep their slaves locked up, which is such a completely preposterous idea that I am surprised I entertained it at all, even at 13.

We explored the site for about an hour, went back home, and never returned.

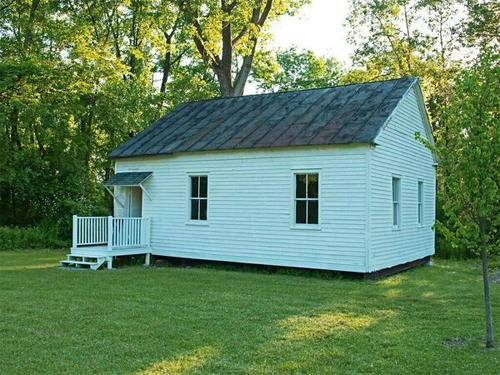

6. The Ichabod Crane Schoolhouse. Again, this is not to scale, it was up near the Van Alen house, about 200 yards away and on the other side of 9H. Unlike the Van Alen house, it was in plain sight and easily accessible. But it was just another old building left to rot along the road (there were several) and it didn’t look at all interesting, so I never tried to see inside it. More’s the pity.

The schoolhouse was built in 1850 to replace the original log cabin schoolhouse. In all that time, the building was never modified to have heat or hot water and the original 1929 wood-burning stove was still there, along with wood flooring, chalkboards, and double-hung sash windows.

According to the website, “It remains an excellent and intact example of a rural, one-room schoolhouse with a gable roof, clapboard siding, and a single pent-roofed entrance. The interior consists of a large classroom with two adjacent cloakrooms – one for boys, and one for girls.”

In real life, Jesse Merwin, a local schoolteacher, taught there, though he may have mostly taught in the log cabin, as Merwin died in 1852.

7. Merwin Lake and Merwin Lake Road. These were, obviously, named after Jesse Merwin, who was locally well-known and is now locally famous, as he and the nearby Van Alan farm were—us locals assert—the inspiration for Washington Irving’s story, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.

According to Wikipedia, “Merwin was teaching at a District School in Kinderhook, where he boarded at the home of Judge William Peter van Ness [this was likely what was to become the Lindenwald estate]. There he met another boarder, a twenty-six-year-old tutor and aspiring author named Washington Irving. Irving and Merwin went fishing and hunting together during that period and became lifelong friends.

“According to a notation by Irving and a certification written in longhand by Martin Van Buren—who was friends with both the author and the schoolteacher—the ‘pattern’ (Van Buren’s words) for the character of Ichabod Crane was based on a Kinderhook schoolmaster named Jesse Merwin.”

Additionally, the Van Alen House and its farm are believed to have served as the inspiration for the homestead of the Van Tassel family. The story goes that—when leaving a party hosted by the Van Alan’s—someone played a practical joke on Jesse by dressing up as a headless horseman and chasing him down the road that now bears his name. True or not, it seems clear that Merwin and this location served as some inspiration for the tale Irving later wrote about the hapless schoolmaster.

This particular, local legend of a headless horseman is fictitious, but Irving most likely drew inspiration from similar Irish and Scottish legends. Even so, that does not rule out a practical joke played on Merwin, nor even the idea that it may have been based on a headless horseman. It might have transpired that a spirited discussion about legends gave someone the idea and, seeing as how Netflix hadn’t been invented and there was little to occupy one’s time back then, someone decided to dress up and scare the life out of the schoolmaster. That’s my story and I’m sticking to it.

Tarrytown also makes a claim, and I don’t dispute it; both could be true. As a writer, I can tell you that inspiration comes from many sources.

To solidify our claim, we named our school district Ichabod Crane and there are various businesses (Sleepy Hollow carpets comes to mind, but that was many years ago) that use some sort of reference to the story.

8. This is the house where Mom, my aunt Ann, Dorothy, and my grandfather Benjamin “Denny” Denison lived in the late 40s and early 50s. This was also about a half mile from my house but, as Denny died when I was just a month old, Mom never took me there. I do have photos of Melinda at the property, however.

9. Charlie Barton’s Gas Station. This was on the far side of 9H across from The Corner where we waited for the bus. Being the only business within walking distance, it figured large in my life and merits its own chapter.

10. The Old Post Road. This dirt road ran parallel to 9H, crossed over in front of Lindenwald, and continued on the other side of the road for a while until it merged with it a half mile later. In the colonial days, it was the main road from NYC to Albany, and in front of the Lindenwald gatehouse, there is a mile marker—put up in the colonial days—with an inscription that reads something like “117 M FNY,” meaning it was X number of miles from New York City. (The number was legible when I was a kid, but I forgot what it was and in the photo I have of it, the number is obscured.)

Mom’s old house, Charlie Barton’s Gas Station, Lindenwald and Aunt Dot’s house were all on the Old Post Road.

11. The stream. I mentioned this in my previous post, and told how a neighbor boy and I followed it to the Kinderhook Creek, which until then we didn’t know was there.

12. The Island. After we found the creek, we discovered The Island, a mound of pebbles and sand rising from the middle of the creek. There was a shallow we could wade to get to it, and this is where we swam until we started going to the Sand Bar and Wagoners.

13. Wagoners. About a mile and half from my house. We went there a lot. What we did at Wagoners is detailed in other chapters, so here I will give a short history:

A man named Adam Wagoner bought the land in 1874 and sold it in 1917 to Dr. Birney. At this moment, I am sitting in a café in Horhsam, West Sussex, wondering how a man who gave up the property thirty-eight years before I was born, and during which time the property changed hands at least twice, came to have his name permanently associated with the local swimming hole. I can only surmise that it must have—for the few people who lived around there—been a popular location as far back as the late 1800s. I can picture a farmer’s son in 1893 saying to his mate, “Let’s go down ‘t the crik in back of old Mr. Wagoner’s place.” And then his friend, saying to his girlfriend some years later, “Let’s go swimming down at Wagoner’s.” And, by the mid-1940s, my mom and her sister trekking the route (or being driven by boyfriends) to that bend in the creek, and calling it Wagoners.

The last I knew, the road to Wagoners was blocked off, and it looked difficult to even get there on foot, and I expect the kids today would just swim in their backyard pool, or at least have their parent’s drive them to a proper beach. I don’t expect anyone living there even knows about Wagoners any longer.

Their loss.

14. The Kinderhook Creek. I started writing this entry by saying how it originated at Kinderhook Lake and flowed… Then I thought, “Wikipedia? Nah, they wouldn’t have an entry for that.”

You learn something new every day:

The Kinderhook Creek is a 49.0-mile-long tributary to Stockport Creek, an inlet of the Hudson River. From its source in Hancock, Massachusetts, the creek runs southwest through the Taconic Mountains into Rensselaer County, New York, and then into Columbia County. It flows through the towns of Stephentown, New Lebanon, Nassau, Chatham, Kinderhook and Stuyvesant to its mouth at Stockport Creek in the town of Stockport.

The Kinderhook Creek has a drainage area of over 329 square miles.

History:

The Kinderhook Creek was known as Pasanthkack by the Mahican Native Americans. Prior to 1667 it was known as “Major Abram’s (Staats) Kill” and “Third Falls.” In 1823 it was called Stuyvesant Falls (now referring to a village on the creek) and after 1845 “Kinderhook Creek.”

The name “Kinderhook” has its root in the landing of Henry Hudson in the area around present-day Stuyvesant, where he was greeted by Native Americans with many children. With the Dutch Kinder meaning “child” and Hoeck meaning “bend” or “hook,” the name literally means “bend in the river where the children are.” A figurative translation is “children’s point.”

The area around the Kinderhook Creek was called Machackoesk by the Native American Mahican Tribe.

All those years I lived there, I had little idea of the history I was sitting on. I wish I had taken an interest sooner.