-

Uncle Jim

For a guy I visited nearly every week while I was growing up, I don’t know a lot about my uncle Jim.

He lived in a farmhouse on the edge of Valatie, NY, with his wife Ada, my cousins Kim and Sandy, my other uncle, Skip, and my grandmother and grandfather. The house was large, with a kitchen, dining room and living room. Off the living room, through an open doorway, was a central hall with the stairway leading to the bedrooms. Through another open doorway was Jim and Ada’s home, a mirror image of Granddad and Grandma’s.

It never occurred to me to question this odd arrangement, or how the home and land came into our family. It just was.

My Dad (Bud), Jim, Skip My family travelled there just about every Sunday, but we always stayed on Grandma’s side, where we had the run of the place. We went there to attend church, walking with my cousins from the farmhouse to the Lutheran Church on Zion Hill in the town. After church. We would sit in the kitchen, with my grandparents, uncles, Ada and mom until the talk got too boring, then we’d roam about getting into mischief.

There was a pump organ in Grandma’s living room, which provided much diversion. One of us would pump the bellows and the others would press random keys. We made a hell of a racket, but none of the adults complained. There was an upright piano in Jim’s side of the house, but we didn’t go there much. No one told us we couldn’t, it just seemed polite to not intrude.

Outside were farm buildings and ancient farm equipment, and this also provided hours of fun. I got on well with my cousins, but the adults remained a mystery. They weren’t gruff or mean, they were just adults and, as such, they occupied a world that we didn’t venture into.

My dad wasn’t keen on talking to us, so it wasn’t much of a surprise that my uncles and grandfather felt the same way.

Actually, Jim appeared more jovial than my dad, though my dad also became more cheerful when exchanging stories with his family, so I don’t know how Jim was with his kids.

What I did know was, we were outsiders. Not shunned in any way, but as the afternoon drew on, it was me and my family who left, and they all stayed, so I was never going to be as close to my grandparents, or Jim and Ada, as my cousins were. But, again, I never thought to question this, or worry about it. It just was.

As I grew older, I learned that Uncle Jim had been a prisoner of war. I found that fascinating, but the idea of asking him about it never entered my mind. Children didn’t ask adults things like that and, if I had, he wouldn’t have told me anything, anyway. My dad told me later that Jim never revealed much about it to anyone.

By the time I became intensely interested in family history, anyone who could tell me anything was gone. My grandparents both died before I was 25, and Jim before I was 30, and any first-hand knowledge of what had happened died with them.

From my father, who knew very little and said less, I got only this:

Jim with my dad c. 1932 Jim was born in 1922. He was 8 years older than my dad, and Dad was 10 years older than Skip. Jim was a typically rambunctious teenager. In the 1930s, the family tended to move between rural upstate NY and Darby, PA, which is on the edge of Philadelphia. They were apparently in Darby in 1942 where, when Jim was 20, he got involved in some trouble. My dad thought it had to do with a car accident. Jim was offered the chance to avoid punishment if he signed up. So he did.

Jim in uniform He went into the Air Force and was assigned to a bomber group as a belly-gunner. At some point during the war, his plane was shot down. According to my dad, Jim put his parachute on upside down and landed in a way that hurt his back. He then had to hide from civilians—who would have killed him if they found him, as they weren’t keen on the guys dropping bombs on them—until he could turn himself in to the German military. He was put in a POW camp and spent the next two years there.

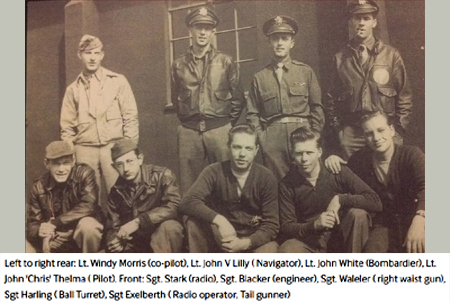

Jim with his crew; bottom row, second from right. When Jim was released and came home, he got all his back pay, and it was this windfall that allowed him and his family to purchase the farm in Valatie. Dad said Jim rarely spoke of his time in the camp, or in the service for that matter, but he did tend to wake up in the night screaming, “The plane’s on fire! Get out! The plane’s on fire!”

And that, for many years, was all I knew.

Jim married Ada, had three children, got a job in a local paper mill and worked there for the rest of his life. He was active in the union, a skilled carpenter and a keen photographer. My grandfather was into photography, and Jim took it up well before I was born. By the time I came along, he had moved on to 8mm film and often—especially at Christmas—dragged the bulky movie camera, with its attachment of four, huge light bulbs that cast a blinding glare through the room, to record the goings on.

All in all, my impressions of Jim are of a good man, honest, upstanding and good-humoured, and I am sorry I never got to know him better.

I was 29 when he was tragically killed at work in an industrial accident. If he had lived longer, I like to think he might have, eventually, answered some of my questions.

When I did become serious about delving into my family history, my aunt, now in her 70s, kindly lent me some of Jim’s stuff, which included an assortment of 8mm movies, all the letters he had received while he was in the prison camp, and an extraordinary book by Ben Phelper called Kriegie Memories.

The movies were as interesting as silent films of people I didn’t know could be. The letters, although a wealth of information concerning my family’s activities during the war years, offered very little information about Jim and his time in the prison camp. The book, however, was a marvel.

One of the many photos taken by Mr. Phelper. Somehow, Mr. Phelper managed to smuggle a camera into Stalag 17B where he, Jim and thousands of other allied prisoners were being held. He also managed to take a whole load of photos without being caught and killed, smuggle them out and get them developed when he got home. He then put them in a self-made, hand-written book and had copies printed. Jim, although he and Mr. Phelper never met each other (it was a large camp), ended up with a copy. How, I don’t know.

The photos are grainy black and white shots, but the book is an astounding accomplishment and, even then, I recognised it as something special. Unfortunately, it did not shed any additional light on what happened to Uncle Jim.

Using hints from the letters, I did some on-line digging, but came up empty-handed.

I don’t fiddle with genealogy much these days. It’s too time-consuming and I have other things to do. But I was searching through my files the other day and thought to have another go with a Google-search. And I turned up gold.

Since my last attempts, a lot of data has been uploaded, and the American Air Museum provided a wealth of information.

James Cecil Harling was enlisted in military service in Philadelphia, on 28 June 1942 “for the duration of the war or other emergency, plus six months.” He went into the Air Corps and was sent to England with the 94th Bomb Group, 333rd Squadron, based in Bury St Edmunds, in Suffolk. On the 27th of September 1943, his plane was shot down and all but one of the crew were taken prisoner.

The crash report was a revelation. This is what was reported:

“Ball Turret, J. C. Harling S/Sgt. A.C

“Kept enemy fighters off until we got the ship under control. He was in his position with only the aid of a belt to support him. The turret door was blown off do to enemy action. He left the ship through the rear hatch of ship unharmed. I put him in for D.F C. [Distinguished Flying Cross] but no word has been received to this date. I think he’s intitled to this decoration.”

The crash report, submitted in or around 1946. He was 21 years old when he went through that, and spent his 22nd and 23rd birthdays as a POW. I know a lot of the boys didn’t want to talk about what they had gone through when they returned home, but I think it’s a shame that I only found all this out long after he was gone.