-

Rabbits

When we were young, each of us received a baby rabbit. I don’t recall when this was, but my little sister got one so she must have been at least two or three, which would make this sometime in the mid-1960s. I also don’t recall where these rabbits came from. I think my grandparents might have had something to do with it, but I can’t be certain.

What I am sure of, however, is the clear memory of the five of us, each with our newly acquired bunny, in the Shop with Dad, who built two cages for them—one for the girl rabbits and one for the boys. He then took them from us, one by one, checked their gender, and deposited them in the proper cage.

This is how we came to raising rabbits.

This wasn’t our first rodeo, by the way. Our parents, when they first married and moved into the house on the appropriately named Rabbit Lane, had rabbits. I don’t recall them at all.

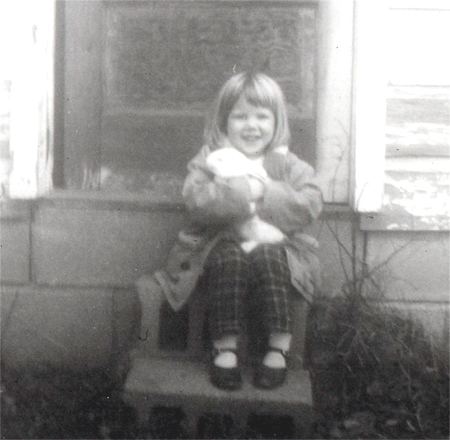

My big sister, in 1955, with the first set of rabbits.In no time at all, litters were popping up in both the boys’ and the girls’ cages and my father built cage after cage in an attempt to contain them all. Where or when the idea of purposely breeding them came from I don’t know. All I do know is that, from then on, rabbits became an integral part of our lives.

At that time, the Shop was not partitioned off, so there was ample room and Dad made good use of it. He devised a system involving rows of cages, stacked in tiers, with sliding trays beneath them and feeders, for water and pellets, in front. It was a factory system, but the rabbits weren’t treated like factory animals. Each rabbit had a name and could count on one of us taking them out from time to time to gambol on the lawn or in the house, even when we had nearly two hundred of them.

They were such a part of our lives that I don’t really recall much about them, they were always just there. And, surprisingly, there is scant photographic evidence of them. I have only a few photos of us playing with them, or of them in the house—but no pictures of them in the Shop.

I recall that the systems put in place to manage them took time to develop, but I don’t recall when we began eating them. By the time I was a teenager, however, it was pretty much routine. Before school, we’d go out to the Shop to feed and water them. During the winter months, this meant pouring boiling water into their dishes to melt the frozen water that was already there, and topping up the hoppers on the pellet feeders. On weekends, we’d pull the sliding trays out, which required at least two of us because they were large and unwieldy and, trust me, you did not want to drop them. What we did do was empty them on the growing pile of rabbit manure out back, which was then used in the gardens.

Preparing the rabbits for eating was pretty much down to me. Dad did it at first, but as soon as I could, I took over the task. The rabbit raising manuals described how to kill them, but it was so inhumane that even Dad balked at it. You were to hold the rabbit up by the back legs and, while it is kicking and twisting, hit it with a crowbar on the back of the neck. Dad tried it but he only wounded the rabbit. And then it screamed. It was a horrific sound that so unsettled him, he thereafter just shot them.

And that’s how I did it. I’d be in the kitchen and ask Mom what was for dinner and she’d say, “Abigail,” or whoever’s number was up that day and I’d get Dad’s .22 pistol and go out to the Shop.

If the weather was nice, I would take the rabbit outside, let it play on the grass for a bit and stroke it until it settled down. Then I’d pull the gun out, put the barrel between the rabbit’s ears and pull the trigger. I figured, if you were destined for the pot, that would be the least horrible way to start your journey.

From there, it was a short trip to the gutting table in the shop. Skinning took little time as we weren’t concerned about the pelts. We did try to cure some early on, but the results were less than satisfactory, so I’d just pull the skin off, slit the belly, clean it out and that was that. I have no memory of what we did with all the waste. There must have been a bin or something, and it must have needed emptying and cleaning on a regular basis. That seems to me to be a really gross job that would stick in your mind, but I have no recollection. As for what we did with the waste, I suppose we burned it. We burned everything back then.

Rabbits, it transpires, are a versatile food. They are a lot like chicken in that you can boil them, fry them, roast them or make stew from them. And, I suppose, they even taste a bit like chicken. In this manner, we grew up, routinely eating our pets, and thinking nothing of it.

And it wasn’t only rabbits we ate.

There was a big freezer in the Shop in those days. Why, I can’t say. It was often empty and there was little use for it, until a friend of Dad’s started trapping raccoons for their pelts. He kept the carcasses to sell to the migrant workers—the only people who would eat them—but he had so many he needed a place to store them. So, Dad let him use our freezer and, in return, he said we could take a raccoon or two whenever it suited us.

It suited us fairly often, as I recall.

Raccoon is not as versatile as rabbit. The tough, stringy meat was only good for stew, but raccoon stew was frequently on our menu. Mom had to boil the carcass twice to leech out the fat and soften the meat up. Then she’d let it simmer in the stew. The results were tasty enough and we all liked it. Once she brought it to a church supper. Pastor Isley knew what it was, but he told her to not tell anyone else. She passed it off as beef stew, I think.

That would make sense, as that was what it tasted most like—a stringy, tough cut of beef.

One day, Dad was barbecuing, and he took a small raccoon, cut it up and marinated it. Then he roasted it over the barbecue. The results were satisfying. It was lighter and more flavorful. Then his friend, when he next looked in the freezer, asked Dad where the possum had gone.

In addition to eating the rabbits (and other, random wildlife) we also gave them away as pets. One time, I made use of one in a magic show at the Cub Scout Pack meeting by pulling it out of a hat. They were handy that way.

Due to the continual inbreeding (the original five were all from the same litter) we started getting mutations, so we began bringing in other rabbits to breed with the indigenous population. As I recall, many of these outsiders didn’t fare well, at least in the breeding department. There was a strange resistance to them, which kept the breeding program from becoming a resounding success.

They were also, sometimes, less pet-like than the others. I recall that more than a few of them bit and kicked, and there was one particular rabbit—a bog-standard, brown bunny named Charlie—who was so mean I had to wear gloves to handle him. He was the only rabbit this was required for, and the only rabbit I actually enjoyed shooting in the head.

The inbreeding, therefore, continued, and manifested itself in several ways. One was the angora rabbits. These rabbits were mega-fluffy, like big balls of brown chiffon. They were friendly enough, but we couldn’t breed them. Early on, we discovered that they would eat their litters, so we stopped breeding them and just gave them away as pets. Or ate them when their number came up.

(By the by, I say that as if we had a system for selecting our next dinner, but as far as I know we didn’t. Mom just randomly picked a bunny in her head.)

Another drawback of inbreeding was a disease that would, strangely, make the rabbit tilt its head until it twisted a full 90 degrees, with one eye staring at the ceiling and the other at the floor. It was weird and they always eventually died, so we began killing them as soon as we recognized the first signs of sickness.

The other thing I can’t recall is when we stopped. I have evidence of there being rabbits in the house as late as 1973, the year I graduated high school, so they were still around until the mid-1970s, I expect. I can only suppose that we slowly stopped breeding them and just whittled the population down.

I do recall a photo of my brother holding a huge brown rabbit that we called Grandpa. We believed he might have been one of the original five, or at least a first-generation offspring. I also remember that, when the photo was taken, Grandpa was the only rabbit we had left.