-

Dog Days

Ah, the Dog Days, the Fag End of summer, a final flurry of sultry sun before the year begins anew.

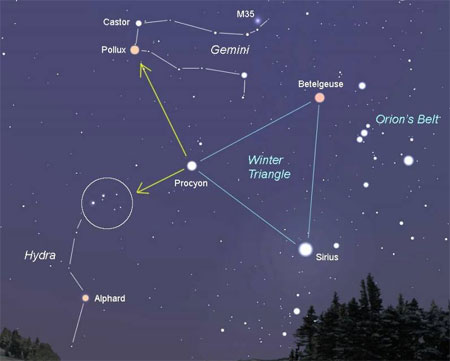

As a child, I had no idea what the Dog Days meant. I took it to mean those days where it was so hot the dogs would just lay on the porch panting. It wasn’t until I grew up that I found out it came from the Romans, who referred to the end of summer as “dies caniculares” or “days of the dog star,” which was when Sirius would appear in the sky just before the sun. This saying, over the years, was shortened to “dog days.” And moved, by the way. The appearance of Sirius happened, in Roman times, at the end of July, and the modern term Dog Days referrers to the end of summer, which is the latter portion of August. Therefore, I still contend the image of a panting dog lying on a shady porch is a more accurate and visual representation of these long, hot days than “die caniculares.”

For the budding astronomers. I remember it as a bittersweet time, a pause between two worlds: summer, where I wanted to remain, and autumn, where I knew school awaited. Summer still held the world comfortably in its grip—you knew this by the tar, soft and hot, under your bare feet as you walked the McAdam strip that was County Route 25—yet autumn was sinking it’s tendrils in, evidenced by the occasional red leaf on the maple tree, the harvesting of the wheat field bordering the path to Wagner’s swimming hole, the withering potato plants (having been sprayed with poison to ready the potatoes for the digger), and the cool, clear nights.

The creek, however, remained warm, as warm as it would ever be over the course of the year. In the spring it ran fast, clear, and ice cold. In the summer, it slowed, the level dropped, and where it swirled in the bends, it was simply chilly. But during the dog days, the creek ran sluggish and warm. We’d swim a lot, splashing in the green water, while the occasional fallen leaf drifted lazily in the stagnant pools. The unrelenting sun assured us summer was not yet over, but the angle of its rays, and the tired green of the copse surrounding the creek, told us its days were numbered.

I recall camping out at the Sand Bar. We never camped at Wagner’s swimming hole; that was way into the woods and that would be too scary, but the Sand Bar was next to the village of Stuyvesant Falls, so it seemed safer. We’d sit around a small fire on the cliff top talking about nothing, then in the early hours, descend to the sandy beach to skinny-dip. The cool night made the creek feel warm as bathwater, and we’d swim, taking in the slightly rotten scent of stagnation, the smell of dying leaves, and a faint tang of woodsmoke. Around us the cliffs—a deeper black in the darkness—rose from the water’s edge, topped with the spiky silhouettes of pine trees sharp against the night sky, all under the canopy of the Milky Way, glowing like diamond dust (a sight that is hardly visible these days). And unseen, but hanging above it all, the knowledge that another morning was about to begin, bringing us one day closer to September.

We were lucky, however. The countdown to school also coincided with the countdown to the Chatham Fair, or more exactly, The Columbia Country Agricultural Fair. It was an event eagerly looked forward to—a final hurrah, a burst of excitement, an annual ritual of fun—to usher us into the next school year.

Up next…