-

Cycles of Change

I read a book recently that was published in 1959. None of that is relevant, however. What is relevant is that, in the narrative, there are characters who reminisce about things from their childhood that “kids today” are never going to know about. And that got me thinking: I’ve written a lot about what has changed since I was young, but the generations before me saw even more, far-reaching changes and, although I did not personally experience them, it would be relevant, and important, for me to highlight some of them.

It is strange to think that, in the early 1900s, around the time my grandparents were born, things existed pretty much the same as they had for hundreds, even thousands, of years. Homes were heated by a fire, and the fireplace was the focal point of family life, just as it had been since the days their far-flung ancestors sat around the fire in their cave. Horses were, as they had been since the beginning of recorded history, the main source of transportation. With no television or radio, a piano was often used for entertainment. (Even when I was young, there were a lot of old, upright pianos hanging about.) People wrote letters by candlelight, or the light of a kerosene lamp, by dipping their pen into an inkwell and scratching it over a piece of paper. And in Britain, the pub was still an important part of life.

Your home entertainment centre, from 3,000 BC to 1940. All of these things existed back then, and many even more recently, and although technological advances had been made, life was pretty much the same as it had been since civilization began: you heated with fire, you rode a horse (if you were lucky), you used the modern equivalent of a quill pen to write, and you amused yourself by telling stories around the fireplace, playing an instrument, cards or various other types of games, or going to the pub.

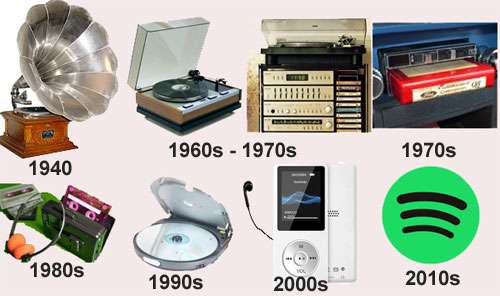

How we listened to music: c. 1700 to 1940. None of that exists any longer. I think that is significant because, although change is constant, the rapidity of change in our time has desensitized us to it. No one mourned the passing of Betamax (except me because, yeah, I bought one), or the VHS recorder, despite how central they had become to our lives during their brief popularity. In my own life, we’ve gone through vinyl records, 8-track tapes, cassette tapes, CDs, iPods and Spotify, while a farmer in the 1800s might play the fiddle his father had left him (who got it from his father) because that was the only source of music available to him from the time he was born to the time he died. We measure changes in years; before the 1900s, they were measured in centuries.

How we listened to music: 1940s – today. Think about it: horses. For millennium, they were part of the scenery, and an entire industry—leather workers, breeders, blacksmiths, carriage makers (and drivers), stable boys, and many, many other livelihoods I am unable to imagine—revolved around them, and in the space of a generation, they were gone, never to return.

Ditto for fireplaces. No longer would families gather ’round the hearth in the evenings, or experience (as a character in the book referred to above reminisces) the smell of woodsmoke in the house. Hers, she thinks sadly, is the last generation who will have that memory. Another character, a younger one, notes the increased use of cosmetics since the introduction of electric lights. Apparently it was easier to look pretty in the dark.

Horses were everywhere. It was so bad, they looked to the automobile to save them; now we need something to save us from the automobile. But this points out another seismic change related to fireplaces, and the candles and lamps used to light homes: electricity. Again, within a very short space of time, candle-makers, lamplighters, and horse-drawn coal carts were all gone. We can’t imagine living without electricity. It’s unfathomable. And if we were forced to spend the night in a home without power, I suspect we’d be bored and frightened.

What kept people from being bored and frightened back then were evening amusements. As noted above, pianos were very popular, even in the less well-to-do homes, and there was always someone nearby who could play it. In addition to music, there was a vast array of parlour games, many of which have, sadly, been lost.

Although handwriting— using a pen of any description to write on a physical piece of paper—hung around for a long time, it is pretty much out of fashion—and memory—now. Despite the ballpoint pen having been invented in 1888, and the fountain pen in 1884, people still mostly wrote with a pen they needed to dip into an inkwell, just like the monks of the fifth century did. In fact, dip pens were still being used in schools up until the 1960s. By the time I was writing with a pen, however, the ballpoint had taken over.

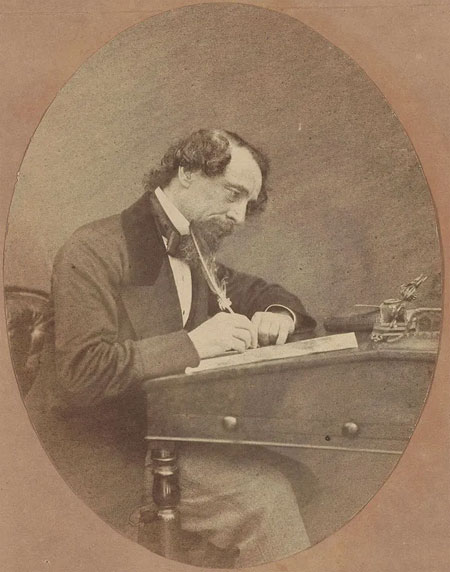

Quill pens; they were good enough for Dickens. And then, of course, came the typewriters. They, too, had been around for quite a while, with the first commercial models having been introduced in 1887. They were slow to catch on, but they really took off in the 1930s, and by the time I was in school they were ubiquitous. When I took typing in eleventh grade, however, they were still using manual typewriters, despite the electric typewriter having been invented in the 1920s. But manual or electric, they all went the way of the dip pen by the end of the 1980s.

Today, children are not even taught how to write in cursive, as it is expected they will use a keypad on their tablets or phones and use sentences like, “BTW R U cmng DM me C U L8R” It makes me weep.

The introduction of electricity, central heating, radio, and television changed society in many way, but none so dramatically, or mourned over, than pub life in my adopted home of Britain. In years past, the pub was the focal point of the village or the neighbourhood, and young men looked to the day they could follow their dads into the pub and carry on the tradition. But boys don’t want to follow their dads into the pub any more and they haven’t since the introduction of the television. On both sides of the Atlantic, TV made hundreds of thousands of upright pianos redundant, and in Britain, it put an end to hundreds of years of pub life. Over here, the news is full of lamentations about how many pubs have closed, and how many have been turned into convenience stores, homes, or demolished. There are societies and movements who push against this tide and try to hold onto the old traditions, but the sad truth is, the pub—as it has always been known—no longer exists. It’s gone, and it’s not coming back, just like horses, wick trimmers, and playing Squeak Piggy Squeak around the fire.

Oh, and indoor plumbing. I forgot about indoor plumbing!