-

The March of Time

For those of you who do not follow my other blog, I have recently finished The Talisman series, an eight-book, YA Fantasy/Adventure that explores the history of Britain through the eyes of two twenty-first-century boys who just happen to have the same names as my grandsons.

It’s a decent series, good, solid writing, even if I have to say so myself (which, yeah, I kinda do) and you could do worse than giving it a try. I mean, it’s only £0.99 on Kindle so, really, you don’t have much to lose.

But that’s not what I want to talk about.

With that project over, I am now full-time on The Patriarch Diaries, which does not mean this blog but, rather, the book I have always planned to create from this blog.

The book is to be a combination of family history, legends, general reminiscence, and as much of my life story as I can pack in. The General Reminiscence section is pretty much what this blog is made up of.

But that’s not what I want to talk about.

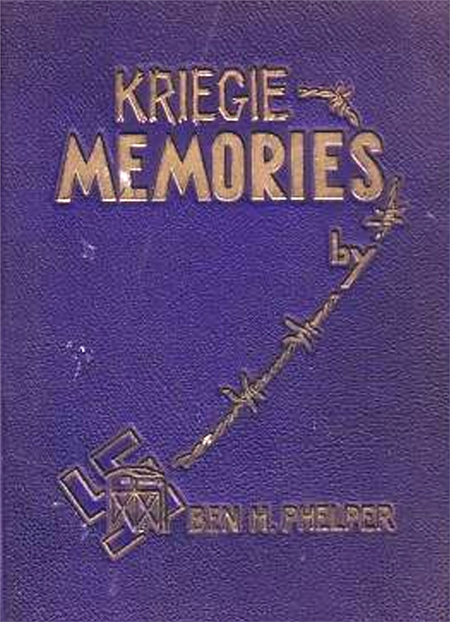

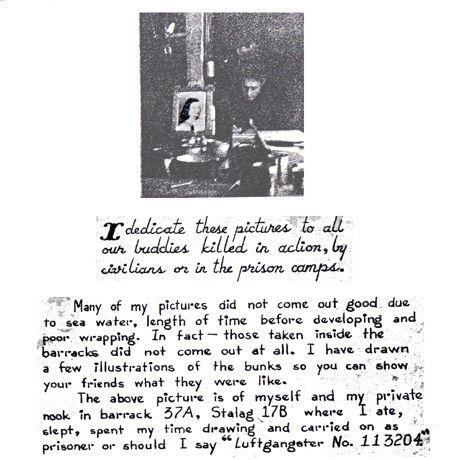

One of the first tasks I undertook was a side-project involving Ben Phelper’s Kriegie Memories, a book he wrote about his experiences in Stalag 17B during WWII. It’s an amazing book, recounting a story that should not be forgotten, and I wanted my Grandkids to have the opportunity to read it.

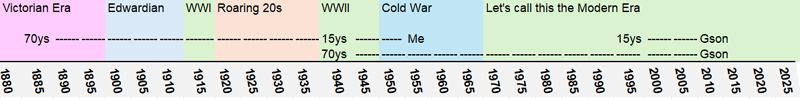

My oft-repeated quip about this (and other ramblings down memory lane) is that my grandchildren regard those stories the same way I regard stories about the Victorian Era. Ha Ha. Except it’s true.

World War Two began fifteen years before I was born. I grew around people—young men in their 40s and 50s—who fought in that war and had first-hand knowledge of it. But for my G-kids, that was 70 years before they were born, and if you go back 70 years before I was born, you hit the Victorian Era.

WWII: just as relevant to my Grandchildren as the Victorian Era is to me. Granted, I knew people who were born in the Victorian Era, and who fought in World War One (not so uncommon when I was growing up) but they were old people, with stories I didn’t, at the time (and I could kick myself now) find relevant.

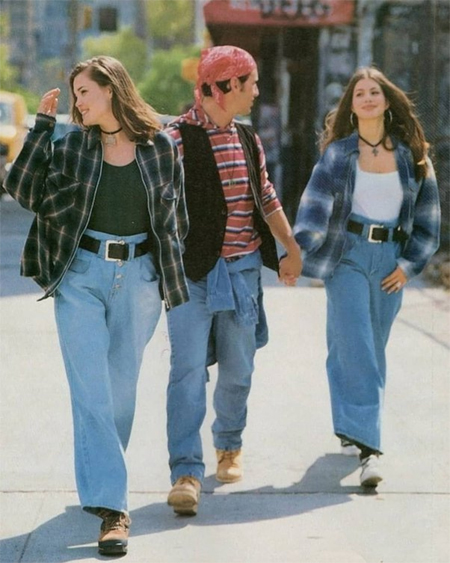

How people dressed when my grandchildren were born.

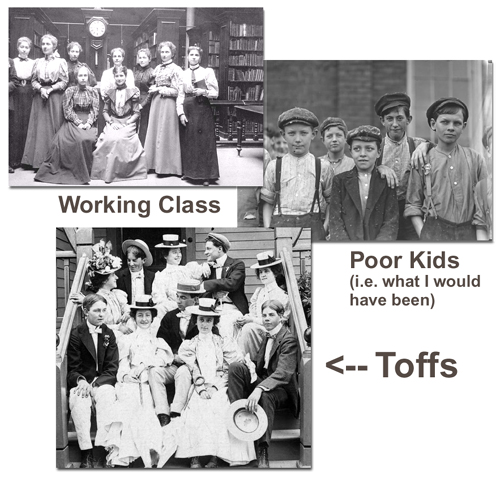

How they dressed 70 years before they were born. And so, The Patriarch Diaries, my attempt to record as much about my life, my family history, and what life was like in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s as I can, and present it to my grandchildren in the knowledge that it will be totally irrelevant to them.

How people dressed 70 years before I was born. But someday, when they’re my age, they may feel differently, and at least they will have the chance to find answers to the questions I wish I’d had the foresight to ask my grandparents when I was young.