-

Gadgets – Part I

To follow up my dissertation on the progression of the World Wide Web, I thought I’d take you on a tour of the gadgets I used to own, demonstrating how they became more complex, decreasingly expensive and of greater use as time went on.

As soon as it became possible, I turned to technology to aid my writing. This was because my handwriting is totally illegible, even to myself. I wrote in notebooks because I had to—there was no other way of doing it—and procured a typewriter at my earliest opportunity. This helped when I was at home, but writing al fresco remained a problem for some time, mainly because, as a young, aspiring writer, I had a predilection for graveyards, where I could perch on a monument and ruminate on life, or my latest crush, and using a typewriter—even a portable model—under those conditions was out of the question, leaving me longing for a suitable gadget that wouldn’t be invented for many years to come.

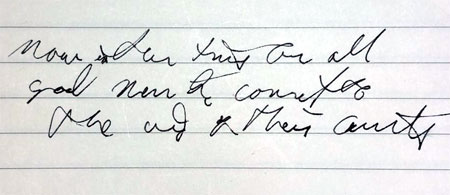

Sample of my actual handwriting. My initial foray into the world of technology occurred in 1979, when my erstwhile wife bought me a computer toy for Christmas. It was a blue, plastic affair, with a small panel of red lights and some sort of input method that allowed you to program how and when they blinked. You could make stars and squares and bursts, and I had hours of fun with it. Primitive as it was, it made me fall in love with programming, but did nothing to resolve my writing-on-the-go issues.

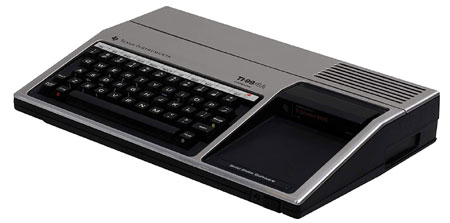

My first real computer—a TI 99/4A—came two years later. While everyone else was using the Commodore 64, I was playing with a wedge-shaped keyboard, wired to the TV and plugged into a cassette recorder. All I can say is it worked, and with it I learned how to program for real, and delved into the world of two-, three- and even four-dimensional arrays, but I still wrote in notebooks when I was out and about.

My first computer. In addition to illegible handwriting, I also suffer from an inability to spell. This deficiency plagued me like, well, the plague, back in those days when there was no cure. (While typing this, the spell-checker picked up four misspelled words in the previous sentence—and two, so far, in this one—so the plague haunts me still, but at least now I have an antidote.)

By the mid-1980s, technology was addressing this oversight, and in 1986 I bought a WP Brother Typewriter with a daisywheel and—wonder of wonders—internal memory.

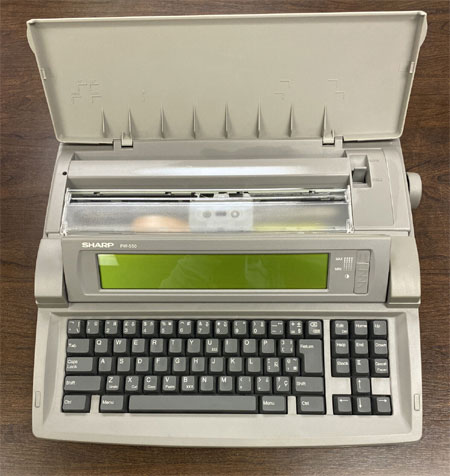

The Ultra-Modern Typewriter.

This is a Sharp model, but mine looked similar.[Quick History Lesson: Until the arrival of daisywheels (and the IBM Selectric ‘Golf Ball’), when you typed, you got courier, fixed-width font. That was your option. With these new innovations, a user could select from a variety of fonts, many of which could print in proportional spacing.

For the youngsters:

This is proportional spacing

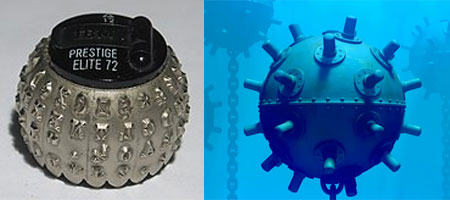

My WP used daisywheels, which were lighter and smaller and easier to manage. The IBM ball looked like a WWII submarine mine with letters instead of spikes (and, of course, it didn’t explode), and it hacked at the page like someone beating you with a mace, but it produced precision lettering.]

LEFT: IBM Selectric Golf Ball. RIGHT: Submarine mine.

Know the difference; it could save your life.

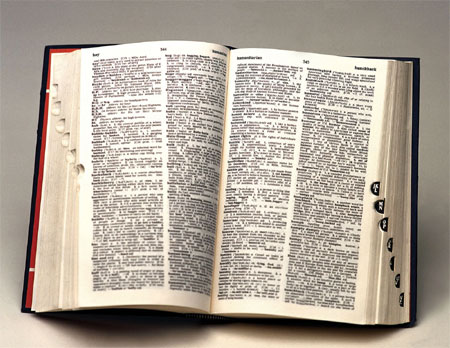

Daisywheel Both of these were remarkable innovations, adding years of life to the sadly doomed typewriter. They did not, of course, address the portability issue, but my WP Brother made the first, tentative inroads toward fixing my spelling. As I typed, the daisywheel remained stationary, and my words would scroll across a little screen above the keyboard. If I typed a word it didn’t recognize, the typewriter would beep, allowing me to scroll back, find it and, with the help of a dictionary (explain it to the youngsters), fix it. When I was happy with the text I had typed, I would press a button and the daisywheel would spring into action, regurgitating all I had entered into the typewriter’s tiny memory banks.

This is a manual Dictionary. It showed you how to spell and pronounce words,

and what they meant. The drawback, of course, was,

if you didn’t know how to spell a word, how could you look it up?By then, technology was progressing faster than I could keep up, or my budget could manage. I suspect there were other solutions available, but they were prohibitively expense, which was why, when I stumbled upon something called an Amstrad Word Processor in October 1986, with a price tag of only $640 (about $2.4 million in today’s money) I bought it. It was a huge investment for me back then, but it served me well until 1992, when I sold it for $100 to a guy from Scotland.

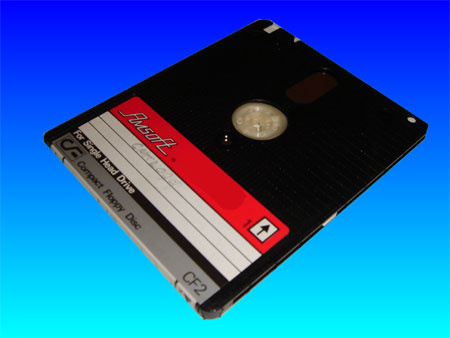

The Amstrad computer/word processor. Unbeknown to me at the time, Amstrad was the brainchild of Sir Alan Sugar, a British entrepreneur. It came with a CP/M operating system and used 3-inch discs, which were a challenge to procure.

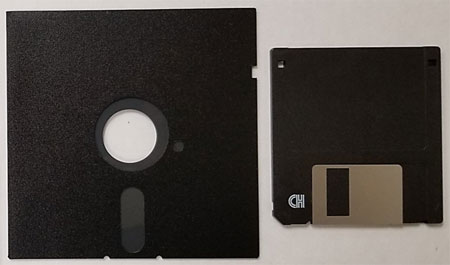

[Quick History Lesson: Computers, back then, did not have internal memory. Data, and even the operating systems, were stored on external, or floppy, discs. These were inserted into the computer, like a CD into a CD player (ask your dad), and the operating system would load, or the necessary data would become available. You would do whatever you needed to do, and copy the results to your floppy disc. When the computer was shut off (we did that back in those days), all the data held in the computer’s innards would disappear.]

Standard 5.25” and 3.5” discs…

…and the Amstrad 3″ disc The discs available at that time were the 5.25-inch or 3.5-inch variety. The 3.5 eventually took over because it was more durable and held more data (1.44 MB as opposed to about .9 MB), but for years the two ran, literally, side-by-side. The 3-inch discs I required were, of course, foreign, and difficult to get.

The Amstrad, however, turned out to be two systems in one. There was the aforementioned CP/M operating system, which allowed me to write applications, and another system-disc which loaded the Amstrad Word Processor. This was my first taste of an actual word processor, and I loved it. I could write and edit text, store it on discs and print out copy after copy if I wanted to. What it lacked, of course, was a spell-checker.

Soon enough, however, one became available. I loaded it from a floppy disc, ran it against my articles, and the program spit out a list of all the words it didn’t recognize. In alphabetical order. All I had to do was go down the list, search for each word, and manually correct it. The program cost $50. I thought I had died and gone to heaven.

Some years later, in 1991, I found myself unmarried and working in IT, and the young woman I was involved with at the time went in halves with me on an actual computer. It was an early Emerson with about 10 MB on the hard drive and less than 1 MB of RAM. It cost $1,099, which was expensive enough that we had to buy it together. (Back in the early days, any decent desktop PC cost well over $2,000, and laptops, when they came out, cost over twice that.) Then we had to fork out $64 for a mouse (have you ever tried to use Windows without a mouse?) and soon after decided we needed more RAM memory, so, back at the store, we bought a single MB RAM chip…for $100.

I paid $100 for that in 1991. To put that into perspective, the laptop I am currently working on has 100,000 times the Disc space of the Emerson, and the RAM alone would cost $8,000. I paid £699 for it last December.

By the end of 1992, both the PC and the woman were history, and I was bereft of technology. I recall staying late at work so I could write on the computers there, which was unsatisfactory, and in no way brought me closer to my goal of being able to write wherever I happened to be.

End of Part I

Coming Soon:

I share a computer with SWMNBN and continue my quest for mobile computing.