-

The Downside of Boredom

I often extol the benefits of boredom and bemoan the fact that kids today don’t know what it is to have great swaths of time stretching out before them with nothing to do—no social media to troll through, no Netflix to stream, no on-line shops to browse. Think of all the creative, though admittedly often mindless, projects that have gone unrealized because commenting on Enema’s new outfit was more important, immediately gratifying, and a lot less of a bother than, say, exploring the limits of your endurance by taking a swig of Listerine and seeing how long you could hold it in your mouth before spitting it out. (True story.)

It was one of these periods of boredom that led me to starting The Tunnels.

I was exploring my bedroom closet and found—if I pulled out the box that held the many pairs of ice skates and moved the Christmas ornaments—I could squeeze into the vacant spot behind it. I was in my early teens, but still tiny, so it was a perfectly sized hiding place. Granted, I didn’t actually need a hiding place, but it was handy to have one, and as soon as that thought settled, a second thought—because it was so blindingly obvious—immediately made itself known and demanded attention, and action: my new hiding place was the ideal location for a secret trapdoor into the basement and (of course) a corresponding escape tunnel.

After spending an hour or so taking precise measurements, I squeezed into the crawlspace (we didn’t really have a basement, just a gap of about two or three feet between the floor of the house and the hard-packed earth beneath) and located the spot directly beneath my hiding place and, wisely deciding to leave the trapdoor idea until later, began to dig. I managed a hole about three feet deep and the beginning of a tunnel before getting bored with it and going on to something else.

But I didn’t forget about it and had soon recruited the only other two boys in the neighbourhood to help. This must have been during the summer because we had a lot of time on our hands, and I recall spending more than a few afternoons in the crawl space, with digging implements liberated from their fathers’ sheds, working on our tunnel.

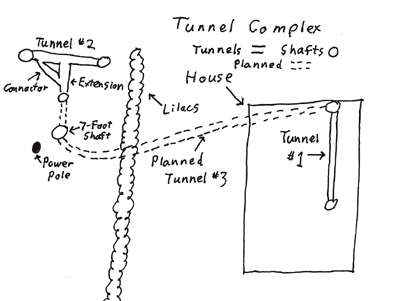

Three of us working in one tunnel soon proved impractical, as well as a waste of effort, so I started another shaft, right next to the foundation wall, to make a second tunnel that would meet up with the first. That this would create an escape tunnel that began and ended under the house never bothered me. By then I had forgotten about the trapdoor and escape route idea and was simply content to dig.

Eventually, the tunnels met, which allowed us the privilege of going into one hole, crawling through the underground passage, and emerging from another hole about 18 feet away. It didn’t take long for the novelty to wear off.

This did not, however, satisfy our interest in tunnelling, so we went outside, to an area beyond the lilac hedge, and started another. It was a lot easier to dig outside and we attacked the task with enthusiasm, and soon had two new holes with tunnels inching toward each other. This time, as the outdoors gave us easier access, we tried to do it right—à la The Great Escape—by including wooden supports but, alas, we had limited carpentry skills, and an even more limited supply of junk wood, so we just dug without any supports, thinking, “What’s the worst that could happen?”

Well, allow me to tell you: one cubic foot of earth weighs 100 pounds, and eight or ten cubic feet suddenly falling on top of you can crush and suffocate you in no time. But we were young and pretty stupid. Mom, however, was not. She had graduated second in her class, was well-read and was, after all (and in my view, this should have been the deciding factor) an adult, yet—despite being totally aware of what we were doing—she just allowed us to get on with it.

We finished that tunnel, dug an extension with a connector tunnel between them, came up with a grand plan for a full network and managed to dig a shaft about seven feet deep before Dad got wind of our activities.

Oddly—seeing as he rarely took any interest in us or our activities—he became concerned enough to visit our construction site one evening.

It was after dinner, while we were all out doing something else, when Dad told Mom he wanted to see our tunnels. She told him it was just a bit of fun we were having, and it wasn’t dangerous, but Dad insisted on having a look. After viewing our work, he concurred that it actually looked pretty sound to him. This put his mind at ease, until he stamped on the ground above one of the tunnels to test its strength, and the whole thing collapsed.

I didn’t find out until the next day when I went out to work on the tunnels and found them caved in. Then Mom told me what had happened, and I had to agree that, yeah, it was a stupid, and dangerous, thing to do, and I went off to find some other project to keep me occupied.

We never filled the tunnels in. The ones outside the lilacs eventually became depressions in the ground, and the one under our house, for all I know, is still there, and the seven-foot hole we just abandoned. We all knew where it was, no one went out there much anyway and, more to the point, filling it in sounded like work, so we just left it.

The only incident that came from this occurred a few winters later, when a huge snowstorm—as they often did—cut our power off. A man from the power company came along and said he needed to look at the power pole, which was outside the lilac hedge, to see what the problem was. Mom told him to go ahead. Then she had a thought, ran to the front door, opened it, and shouted, “Watch out for the—”

“Found it!” came the muffled reply.

Even so, we still never bothered filling it in.