-

Spring

Here in Sussex, the arrival of spring is a welcome event, but it can’t stir up the same amount of unbounded joy as it does in Upstate New York.

Exhilarating as the early snowfalls are, by the turning of the new year, winter has pretty much worn out its welcome. At least that’s how I remember it. December was a fun frolic in the fluffy fakes as they gently covered the tired landscape. Then there was the countdown to Christmas, and that leisurely week leading up to New Year. But, after that, it was just winter.

January was a frozen wasteland, February a dark and dreary slog and March a heartbreak. So, spying a tuft of grass or an optimistic crocus blossom poking through the crusted, grey remnants of the erstwhile winter wonderland was enough to cause your heart to burst with rapture.

Then, of course, it would snow again.

When spring finally arrived, it was heralded by mud. Lots of it. Everywhere. The snow—now lying about in great, dirty heaps where the snowploughs pushed it or where you manually piled it at the end of the driveway—melted slowly away and water trickled and ponds swelled and the creek roared and the lake that annually arrived in the back yard crept closer to the Shop, and our boots made squelching noises as we roamed the fields.

Another early harbinger was pussy willow. In the field next to our house, at the edges of the wood, grew tangles of pussy willow, and the soft, grey buds—that often appeared in February—were generally the first sign we had that spring was on its way. Those days—not quite spring, not still winter— brought the scent of damp earth on the breeze, and a feeling of warmth waiting just below the surface.

In later years, during this brief between time, we took advantage of the steady winds by flying kites. Nothing special, just your basic diamond-shaped kite with a tail, but we’d attach it to a length of fishing twine (the only thing strong enough to withstand the winds) and reel it out until it was hundreds of yards in the air. It was good fun, but difficult to reel back in and often the string broke, leaving lengthy trails of catgut twine festooned throughout the distant forests. And at the rate that stuff decomposes, I’d wager it’s still there.

Spring didn’t rush at us, it crept in slowly, tentatively, making us wary, by degrees, of the certainties of winter, such as the ice on the pond. Since December, it remained safe and solid, but during March it became soft and soggy and probably incapable of holding our weight. So, one of our spring activities was to test this. We weren’t stupid enough to walk out on it, but we did tramp around the edges to see how much we could break off. And once the ice on the pond broke, we knew that winter had lost its grip.

And then, after being held in frozen, suspended animation for what seemed like years, spring would throw off its coyness and gallop in.

In April, the buds on the trees would swell, giving a light green haze to the forest. The crocus would bloom, die, and give way to lilies of the valley, tulips, and a host of purple iris. As the days warmed and the ground solidified, we would help Mom rake the yards, heaping up the dead grass, sticks, twigs, and leftover leaves into big piles and set them alight. One of the scents that still brings the feeling of spring back to me is the smell of wet leaves burning.

With the lawn spruced up, we’d help remove the bags of leaves Mom and Dad had stacked around the foundation of the house the previous autumn to winter-proof it, and we’d turn on the outdoor faucet now that it was no longer in danger of freezing solid and bursting. By then, the peonies were blossoming, the tiger lilies were in bloom, and the rose buds began to open.

And then the birds began to nest. Every year, a pair of sparrows came to nest in the eaves of our house, and we would watch them bring twigs to build their nest, and then bugs to feed their young. We couldn’t see that nest, but some years, if we were lucky, a bird would build a nest someplace where we could see it, allowing us to watch the eggs, which would miraculously turn into baby birds. And we would check on the babies as they grew, feathered, and fledged.

Occasionally, a fledgling wouldn’t make the cut and would end up on the ground. These tiny birds provided endless fascination, until they inevitably died. Every now and again, we would see a fledgling Blue Jay hopping about in the woodland and learn just how protective adult jays can be. Try as we might, we never got near a baby Blue Jay, as the parents fearlessly dive-bombed us any time we got close.

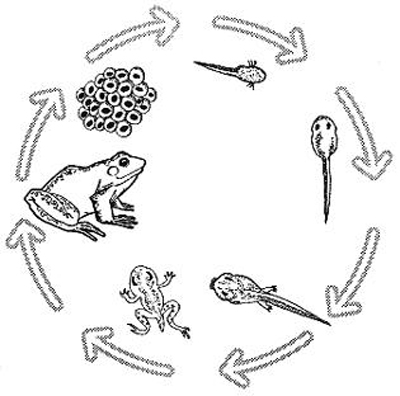

By May, a great, green canopy had spread over the woodlands, and the lilac bushes that surrounded our property, which had been little more than dark skeletons since November, now blocked our view with a wall of leaves and buds. With the ice now finally gone, the frogs appeared in the pond and we spent hours watching them and inspecting their eggs, which they laid in the waterweeds near the shore. The tiny, translucent bubbles would slowly grow, filling with a black dot that, after a week or two, began to wiggle, and then would pop out as a tiny polliwog.

These black, squiggling commas would mass in the shallow end of the pond and, as spring turned toward summer, they would grow, turn from black to green, sprout legs and slowly lose their tails, becoming, by June, bona-fide frogs. Small ones, but frogs, nonetheless. It was an annual miracle that I never tired of watching.

Another spring phenomenon was the tent caterpillars. These tents, comprised of something that looked like spider-silk, would grow in the trees as the leaves matured. Then, when the baby caterpillars ventured out of the tent, they would strip the tree bare. When they eventually left the tent, they rappelled to the ground on silk threads, and we would often see them hanging in the air or feel them landing on our heads. Once this growing and leaving process finished, tent caterpillars were everywhere, providing welcome meals for baby birds.

I also recall the Monarch caterpillars. They lived on the milkweed plants that grew wild all around. Milkweed is called milkweed because of its sap, which looks like milk, but is toxic and can give you a rash if you get it on you. These caterpillars looked amazing, but not as amazing as the butterflies they turned into.

As the days lengthened and the sun warmed, more bugs arrived—mosquitoes, mostly—and a host of wild plants emerged. Dandelions, chicory, wild daises, butter cups, Queen Ann’s lace, and what we called a Poppy, or Salt and Pepper, due to its seed sack that, when young, was filled with tiny, white seeds, and, when ripe, was filled with tiny black seeds, and, when empty, could be popped like a paper bag. I can’t show a photo of one because I have no idea what the real name of it was. (I didn’t’ mean to turn this into a botany lecture, but I’m on a roll.)

Young chicory leaves can be added into salads. The flower buds can be

pickled and the open blooms added to salads. The root can be roasted

and ground into chicory coffee and the mature leaves

can be used as a cooked green veggie. I didn’t know this until just now.

We never tried to eat Chicory; we just ate Dandelion greens.

Buttercups. If you picked a flower and held it under someone’s chin

and their chin reflected the yellow colour, that meant they liked butter.

Why that mattered, I can’t say.Other common sights were Morning Glory, Black-Eyed Susan, Sour Grass, Columbine, Lamb’s Ears, Thistle, and, of course, Brambles, which later in the summer would furnish us with wild berries that we called black caps. A rare plant, however, was the Jack-in-the-Pulpit, a swamp-dwelling plant that I only came across a few times in my rambles.

Morning Glory. That’s what we called it, at least. I found out recently

that it was really bindweed, an invasive weed. I heard somewhere that

Morning Glory seeds can get you high, so I took a bunch of the seeds and

ate them, but nothing happened. Good thing I mistook the Bindweed

for Morning Glory, as Morning Glory seeds are poisonous.

The Bindweed is on the left, Morning Glory on the right;

no wonder I got them mixed up.

I also heard that smoking banana peels can get you high, so I dried

some out in the oven, crushed them up, put them in a pipe and

smoked them. All I got was a terrible headache.

Columbine, which we knew as Honey-Suckle. It’s not Honey-Suckle,

though. We just called it that because if you bit the little bulbs off the

blossoms and sucked the nectar out, it tasted sweet.

Lamb’s Ear, which I just found out in researching this is not actually

Lamb’s Ear. It’s a different plant known as Mullein. We heard that you

could eat Lamb’s Ear, so we boiled some up but found you really couldn’t,

though that was probably because it wasn’t Lamb’s Ear.The final event in spring—a harbinger of summer, really—was the blooming of the lilacs. Lilac bushes bordered our property, and, at the end of May, they all bloomed at once, filling the air with a sweet scent that told us summer was just around the corner.

They were always in bloom on Memorial Day, and Mom would pick a bunch to bring to the graveyard for our annual visit to the grave of her father, Denny. There would also be a parade that day, culminating with speeches in the graveyard, which was why we were there in the first place.

This marked, in our minds, the beginning of summer, and we would usher it in with a barbecue and our traditional swim (see Summer in the 60s).

We were always glad to welcome summer, but it never matched the joy of finding spring had, at last, arrived, and was intending to stay.